- Home

- Shana Mlawski

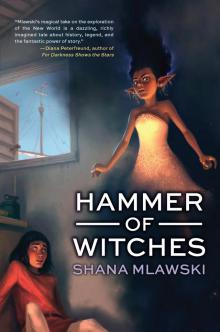

Hammer of Witches

Hammer of Witches Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2013 by Shana Mlawski

Jacket art © 2013 by Andrew Mar

Map in back cover illustration based on Vinckeboons, Joan. Map of the islands of Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. Map. ca. 1639. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, call number G3291.S12 coll .H3. 1 ms. map : col., paper backing ; 50 x 71 cm., http://www.loc.gov/item/2003623402 (accessed September 2012).

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

TU BOOKS, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS Inc.

95 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

leeandlow.com

Manufactured in the United States of America by Worzalla Publishing Company, April 2013

Book design by Isaac Stewart

Book production by The Kids at Our House

First Edition

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data from the print edition

Mlawski, Shana.

Hammer of witches / by Shana Mlawski. — First edition.

pages cm

Summary: “Fourteen-year-old bookmaker’s apprentice Baltasar, pursued by a secret witch-hunting arm of the Inquisition, escapes by joining Columbus’ expedition and discovers magical secrets about his own past that his family had tried to keep hidden” — Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-1-60060-987-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) —

ISBN 978-1-60060-988-6 (e-book)

[1. Magic—Fiction. 2. Wizards—Fiction. 3. Explorers—Fiction.

4. Storytelling—Fiction. 5. Columbus, Christopher—Fiction. 6. America— Discovery and exploration—Spanish—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.M7123Ham 2013

[Fic]—dc23

2012048627

QED stands for Quality, Excellence and Design. The QED seal of approval shown here verifies that this eBook has passed a rigorous quality assurance process and will render well in most eBook reading platforms.

For more information please click here.

To my parents,

who gave me life,

love,

and a lot of books

Table of Contents

Prologue

PART ONE

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

PART TWO

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

PART THREE

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

Twenty-eight

Author's Note

Pronounciation Guide

Acknowledgments

My uncle Diego always said there was magic in a story. Of course, I never really believed him when he said it. My uncle was an old man to me for as long as I can remember, and a bookmaker, too, so his head was always full of one story or another. You could never be sure if he was telling some truth from his past or some legend he had heard along the way. Half the time he probably wasn’t sure himself.

Now I know my uncle was right. There is magic in a story. Real magic. Only when I was a little older and sitting on a shore at the edge of the world did I understand how right my uncle was.

He had almost convinced me one time before. Back then I was seven, an olive-skinned child with thick black hair and a big mouth that was learning to tell lies. We were back in Palos de la Frontera in Spain, in a candlelit closet they called my bedroom. It was summer. The night was sweaty and raw with the smell of tallow and burning wicks.

“Wait, Uncle,” I murmured as I peeked up at him through half-closed eyes. The old man bent in shadows in the doorway. A ball of warm light pulsed on the candle in his hand. “Don’t leave yet. You didn’t tell me a story.”

The ball of light bobbed on the candle as my uncle laughed, and his long shadow laughed across the wooden beams of my ceiling. “All right, Bali. All right.” Each syllable bounced across his tongue. Uncle Diego had always had the perfect voice for stories. He had grown up in Turkey, so his Castilian was stained with shades of his native Greek.

My uncle placed his candle on the floor and lowered himself onto the stool next to my bed. “And what kind of story does His Majesty want to hear tonight?”

“One about Amir al-Katib, of course!”

Of course! My poor uncle had spent the last seven years telling me stories of Amir al-Katib, the noble warrior who fought against his own Moorish people for the freedom of Christian Europe. Best of all, the stories were true. My uncle had known the man in the old times, in Constantinople.

“So His Majesty wants another story about Amir al-Katib. And which one does He want to hear this time?”

“One about the siege of the city. The one where he saved your life.”

“Didn’t I tell you that one last night, Baltasar?”

“Tell the one where he brought you and Father to Palos. No, tell me a new one. Tell me one I haven’t heard before.”

The old man yawned, picked up his candle from the floor, and stuck a hasty kiss on the top of my forehead. “I’m sorry, Bali. It’s late. I’ll come up with a good story for you tomorrow. I promise.”

And he turned to leave. But as he did, a shrill caw like a hawk’s or an eagle’s tore through my bedroom’s open window. The flame of my uncle’s candle seemed to shrink at the sound, and a ragged shadow like a bird of prey trembled across his wrinkled face.

“You know, Baltasar. There is another story about al-Katib, now that I think about it. But if I tell it, you must promise not to tell your aunt Serena. I mean it. There is magic in this story.”

And for some reason, that night, I almost believed him when he said it. “I won’t tell, Uncle. I promise.” So my uncle returned to his seat and began his story:

“Once in Arabia there were two men who killed another. The slain man was innocent, the deed done out of jealousy and spite. The man they had killed was their brother. The two men had coveted his wife.

“When the act was done the elder brother looked down at the slain man and said, ‘Leave him here on the road, where his blood will color the earth. Tomorrow when the sun rises the vultures will come and eat his flesh.’

“Now in Arabia, Baltasar, it is a dreadful sin to murder and a grave dishonor not to bury the dead. But the younger man heard violence in his brother’s voice, so he did not argue. The brothers took a last look at their kinsman, wiped their daggers of his blood, and returned to their homes certain they were safe.

“But they were not safe. For that night, the blood of the slain man clawed toward the heavens, screaming for revenge. And its call was answered. That night a beast sprang from that crimson pool, howling the name of its ancient god. It was the beast known only as the hameh.”

Hameh. I shuddered as the word slithered up my chest. “What is it?” I said almost voicelessly.

“The hameh is a bird, Bali. Black as the sea on a moonless night. Its scream can drive a man to madness, and it leaves a bloody

trail in its wake. And it never forgets its sacred charge. From that moment on the hameh pursued the two men until it delivered justice unto them.”

Somewhere in the distance I thought I heard another hideous shriek, and my fingers curled themselves around the edge of my quilt. Somewhere, I knew, a hellish black hawk was circling the skies, searching, waiting to rend me with its claws and judge me for my sins. Hameh. It sounded like a curse. Like a deadly spell. Like the last warm breath in the mouth of a dead man.

“Uncle,” I whispered, “you said you would tell me a true story. You said you would tell me about Amir al-Katib —”

“I did, Baltasar,” my uncle said, and I heard the sorrow in his answer. I couldn’t yet understand what he meant by that, nor why he told me that story that night. I didn’t yet know that my destiny and the destiny of the hameh had been entangled for many years and would be so for many years to come. And although I suspected it, I didn’t yet know that every word my uncle had said was perfectly true.

“But maybe he’s right,” I remember thinking that night. “Maybe there is magic in a story. Dark magic. Magic that can steal your soul.”

Soon my uncle left and closed the door behind him, and I kissed the Lord’s Prayer into the wooden cross that hung around my neck. It wasn’t long before I fell asleep. And in my dream I thought I heard my aunt’s voice, muffled and distant. “You shouldn’t have told him, Diego. It’s better if he doesn’t know.”

And in my dream my uncle answered, “Do not worry, my love. It is just a story. Meaningless . . .”

There were eyes in my bedroom window. Yellow ones — bodiless and surrounded by smoke. I was fourteen, and it was summer. I had been dreaming about the war.

Hundreds of years ago Moorish armies had taken Granada from its Christian rulers, and from the time I was born our King Fernando and Queen Isabel tried to reconquer it. In my dream I was there at the final battle, surrounded by grim men on tall black horses that stomped, impatient, on the sun-baked ground. Tangled beards hid the men’s dark faces. Splashes of blood defiled their robes. Behind them I saw mountains and burning trees, and the red fortress Alhambra waiting silently for battle.

And it came. The Moorish soldiers raised their voices in one ululating chorus and whirled their sabers above their heads. At once their horses pounded, screaming, past me. I ran from them. I tripped. I felt a sword slicing through my neck —

Then a sudden shriek ripped me from my nightmare, and I awoke to see a pair of yellow eyes shining through my bedroom window. Eyes. Long black pupils bled vertically within them — and beyond them, I could see nothing, nothing.

I groped behind me for the quill lying on the stool next to my bed. As sharp as it was, it was the closest thing I had to a weapon. I grasped the thing in my fist as if it were a dagger, but before I could do anything with it, a whispery voice drifted in from outside.

“Be calm, my shadow,” the whispery voice said. “Shh. Now, do you see him?”

The yellow eyes twitched up and to the side as if listening, not to their questioner but something farther in the distance. Holding my breath, I listened too. Over the sound of my heartbeat throbbing in my ears, over the light trills of humming crickets, I could hear urgent shouting. The yellow eyes listened to them intently, floating bodiless in gray wisps of smoke.

I pushed myself upright on my woolen mattress. “Who are you?” I said in what was supposed to be a whisper.

But the question came out louder than I had meant it, and the yellow eyes snuffed out like two candles. A gust of wind sent a nearby lemon tree into a tumult. Heavy footsteps clanged down the dirt road near my house.

“They’ve found us!” the whispery voice cried from outside. “Quick! Quick! We must go!”

“No, wait!” I exclaimed. I flung my quilt from my legs and lunged for the window. A puff of smoke burst in front of me, filling my nose and the back of my mouth with the scents of cinnamon and incense. I tried to cough the smoke away, but no use. In an instant the smells overpowered me, made me dizzy. I fell back against my pillow.

“No,” I think I murmured. The sound of birds’ wings beat in my ears. “No. Please. Wait. Come back.”

The last thing I saw as the world darkened was the wild image of a bearded man whispering a sentence in a foreign tongue. In vain my mind grasped at his words. Then I plunged into a restless sleep, unsure if I had ever been awake or not.

By the next morning my memory of the night had faded, as dreams do. I spent most of the day napping in my Uncle Diego’s bookmaking workshop, slumped over the manuscript I was supposed to be ruling for him. Dream or not, my experience with the yellow-eyed demon had exhausted me. Even if it hadn’t, the workshop’s stagnant air — hot from summer and vinegary from curing — could fatigue even the world’s most energetic apprentice.

Of course, I had never been the world’s most energetic apprentice.

“Bali.”

Still dull with sleep, I mumbled some insult and covered my head with my arms.

“Bali. Baltasar. Your ink.”

I opened my eyes just in time to see my inkwell sliding off the edge of my slanted desk. In a moment of insanity I threw myself sideways to catch it. Mistake. The sound of my stool’s legs scraping against ceramic tiles was the last thing I heard before I, my inkwell, and all my papers went crashing down onto the tiled workshop floor.

My uncle Diego appeared above me, his smiling face outlined by the brown boughs that supported the roof above him. Though his white head was balding and his green eyes hidden by wrinkles and spectacles, he always gave the impression of an overgrown child.

“This is good, Nephew!” My uncle put his hand on my head, supporting most of his arthritic weight on my skull. “If you don’t make it as a bookmaker, you can always become an acrobat.”

Underneath him I rubbed my bashed elbow with the bony base of my hand. “Make sure it doesn’t stain the grout,” my uncle said. He took a damp cloth from his desk and dropped it onto my face.

Frowning, I peeled the rag off my face so I could see how much grout there was for me to clean. It wasn’t pretty. The workshop’s tiles, once white and hand-painted with blue and red floral patterns, were now covered with splotches of sooty ink. Worse yet, the papers I had spent the last week painstakingly ruling by hand now lay crumpled and ink-spattered under my stool.

“What a mess,” my uncle agreed as I bent over to start cleaning. “You’re worse than Titivillus. You know that, Bali?”

“Titivillus?” I said with a false innocence. In reality, my uncle had told me that story maybe a thousand times — maybe a thousand times that week.

“Titivillus is an imp, Bali. A demon who would sneak into scribes’ workshops and ruin their work when they weren’t looking. And whenever a monk wrote the wrong word in a manuscript, he’d know that Titivillus was to blame!” My uncle put his hand around his chin. “But I may have told you this story before.”

“Maybe.” I smiled. “Once or twice.”

Chuckling, the old man picked up a quill and returned to his slanted desk, where a long piece of parchment waited for him. Hundreds of ornate black letters shimmered, wet, across the page, and a gold-leafed letter T gilded the upper left corner. A wooden contraption used to stretch leather book covers hid most of the table next to him, along with various awls, brushes, and lacquered boxes. This was the future Diego was preparing me for — the aproned future of the bookbinder and scribe. It wasn’t the most exciting future, to be sure, and it all but guaranteed that my old age would be as hunched and nearsighted as my uncle’s. But I supposed crooked hands and boredom were a small price to pay for not having to toil in the fields or on a fishing ship slaving in the river that connected Palos to the sea.

When I was done cleaning up the mess I had made, I said, “Tell me this, then. If the demon Titivillus made me spill my ink, why didn’t he have to clean it up?”

My uncle didn’t even glance up from his work. His face was so close to the page he was inking that I c

ould see a white whisker from his nose scraping against the parchment. “That is a good question, Bali. It must be one of the advantages of being a demon.”

I smirked at him. “You ought to tell the demon I saw last night. It’ll be glad to hear it.”

“I hope you’re not talking about your aunt Serena, Nephew.”

“No! It was a hameh, actually. You know: scary yellow eyes, ‘a scream that can drive a man to madness’—”

My head snapped up at the sound of a sudden, splintery crack. My uncle had driven his quill right through the page he was working on; part of the tip had snapped off near the end.

The man squeezed the pen harder into his fist, then realized what he was doing and placed it on the table with both hands. “‘Hameh’?” he said in a carefully measured tone. “Where did you ever pick up that word?”

I scratched a spot of ink off my face. “You told me, Uncle. Remember?”

The old man’s hands relaxed noticeably around his quill. “Yes. Yes, of course. So what did this hameh of yours do?”

“Not much.” I got up from my place on the floor and walked to the window to wring out my now-filthy rag. “It was probably just a dream. Except . . . ” I crumpled the rag into a ball and patted my other hand against it. “Except I could smell spices. Cinnamon, maybe. And I thought I saw someone.” I replaced the damp rag on my uncle’s desk. “Never mind. Forget it.”

My uncle, however, was clearly not going to forget it. In a twitchy, arrhythmic manner, he tapped his broken quill against the side of his desk. Finally he said, “Go inside the house, Baltasar. I think we’re done for today.”

Done? It took my mind a moment to recognize the word. “Done? You mean with work?”

“Yes. That is exactly what I mean.”

My uncle vaulted off his stool like a much younger man, and before I could figure out how to respond, he was pushing me out the workshop door. Now I was outside, overwhelmed by sunlight, and slouching on the clay steps that led down into our garden. A pure blue sky filled most of my sight. My uncle’s gaze arced over it, as if searching for a hameh.

“Go in the house, Baltasar. And don’t leave until I tell you to. And don’t speak a word of this to your aunt. Promise me you won’t speak of this to her.”

Hammer of Witches

Hammer of Witches